THE SEASON OF IMPORTANT THINGS

Sometimes I wake up in a place completely different from where I went to bed.

It happens rarely, but more often than it should. I've tried to find the reason for it, polish my technique, but there’s just as much mis-awakening. My dentist appointment in Kyiv gets fucked.

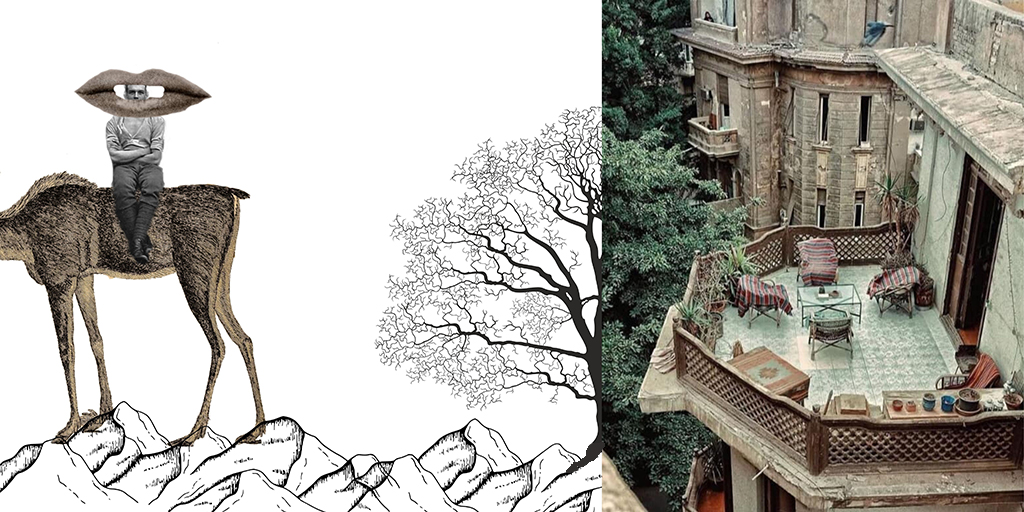

Here, in Casablanca, I usually wake up to the sound of birds flapping against the window. I don’t know why they do it. They fly against the glass, then stagger on the balcony in a daze and embarrassed. I can certainly share their embarrassment, I suppose, while I let the smell of coffee, wafting in from the kitchen, spread out in my nostrils. I love waking up here. Of all the lives, this is my favourite. And it is so not only because here, after breakfast, we swing a dash of Pastis into the coffee. Nor because the bar owner from downstairs, Pierre, a calming presence despite his deliriousness, stares fixedly at a spot on the wall every Wednesday, expecting it to emanate his grandfather who had gone missing in the city. I like his conversations with that spot – he only does it on Wednesdays when there’s a weather front.

You open the coloured, double glass door wide open and enter. You smile and hold the flower-gilded mug you so brazenly haggled over at the market last year. You sit down and talk to me but I can’t hear you. I can’t hear your voice. It hasn’t arrived to me yet. Let’s go and have breakfast on the balcony, I suggest, when your lips stop moving for a moment. And in the meantime, I wish Pereiaslav would put off calling me for a while, after all we still don’t know about the venue of the memorial event for Taras Shevchenko, and anyhow, there will be fifteen of us at most, including the cello trio, so the winter-weary Ukrainian spring can wait.

By the time we settle on the balcony, I’m fully there. I can feel your lips on my neck and hear you swear in joy when the fish fry arrives. I can see the unbearably giddy retriever, Aziza, knock over the son of the fish fry seller in front of the gate and I see myself head to the kitchen to prepare something for breakfast instead of the fish that landed on the pavement. As I fry the bacon, the headline of the memorial evening for the Ukrainian polyhistor, Shevchenko, pops up in my mind, tragedy floating lightly in the air like a sandstorm disguised as a whiff: “The verdict of Nicholas I of Russia: «Under the strictest surveillance, without the right to write or paint»”.

I have always thought that if you come and go between parallel lives, and you do it in such an unpredictable way, then this whole thing at least would have the advantage that while you’re in one, then you don’t think about the other, nor do you feel guilty, or miss anything from the other. But I do! What a load of bollocks! Who in their right mind would want to think about the April schedule of a cultural centre in Pereiaslav, while chilling on a balcony in Casablanca?

Music comes up from the street. This music is like something that you have to savour and slowly get to because it’s too hot or too spicy, even though you’d like nothing more than gobble it up and even rub it into your clothes for it to dry into so that you can feel it for a long time.

You're angry about the fish, I try to calm you down, you rattle on, "come on, let's eat something greasy", I say, I look at you, we eat, we laugh, we get dressed, we're almost ready to leave.

– Isn't it nice here? Peaceful and brave. If I don't move, it's as if never embraced forever. One evening we could sit out on the balcony, you, me and time, and condense infinity into a dinner”, I say.

– I’d prefer some

grilled meat, you say.

You look at me. You want to understand me, but you’d

rather I kept silent. You think that I always obfuscate what’s obvious and

calm. You want nothing but silence, presence, cuddles and play. What you get

instead is the shadow of my eyes, which tell the story of a windy, Ukrainian

afternoon in that dark room, cosy but cold, where I went to bed last night

before waking up beside you here. The room where I abandoned that unfortunate

humanist, the cello trio and everyone who had been my life for so long.

It all started two years ago. Pereiaslav suddenly turned grey, jaded and suffocating and nothing would add colour to it, not the memories, nor any plans. Then, one indifferent night, I went to bed and woke up beside you in the morning. In my parallel reality. It was fantastic. It was liberating. When I opened my eyes, I saw the huge, green balcony for the first time, and the centuries-old tree which so consolingly enfolds passing. (In truth, there was a short detour for a few weeks in a tiny, Norwegian village but that must have been a glitch.)

And now I live in two realities. But I’m not present in both. You can feel it when I’m not really here, even though you can see me. You hate it, I know. It’s the fulfilment born out of absence, and an absence provoked by fulfilment. But most of the time I have no idea where I’d be waking up the next day and why there of all the places. What keeps me here and what drives me away? The place of awakening is never certain.

As we run down the stairs and turn out from the square onto the wide street leading to the salty sea, I sense a thought rolling around in me, soon I have to make a decision. Couldn’t I bring Shevchenko to Pierre’s? They would stare at the spot on the wall together. Shevchenko has a 200-year head start and some experience with the dead, Papa Pierre might listen to him better and emerge if this unfortunate national hero speaks to him nicely. I would give him some paper, I’d let him paint and write freely. It would be better for him than a memorial evening, no doubt.

Meanwhile, we'd be grilling bloody meats on the balcony, until they are crisp, hoping the smell would lure others into this life.

(English translation: Orsolya Polyacsko)

FONTOS DOLGOK ÉVSZAKA

Néha

előfordul, hogy egészen máshol ébredek, mint ahol lefeküdtem.

Ritkán, de gyakrabban, mint kellene. Próbáltam megfejteni

az okát, csiszolni a technikán, de nem lesz kevesebb a félre-ébredés. Baszhatom

az időpontot a kijevi fogorvosnál.

Itt Casablancában általában az ablaknak csapódó madarak

zaja ver fel. Nem tudom, miért csinálják. Nekirepülnek az üvegnek, aztán

zavartan szédelegnek a teraszon. Mondjuk a zavartságukon tudok osztozni,

miközben engedem, hogy a konyhából beszűrődő kávé illata elheveredjen az

orromban. Szeretek itt ébredni. Minden életek közül ez a kedvencem. És nem csak

azért, mert itt reggeli után egy mokkányi Pastis-t billentünk a kávéba, vagy

mert Pierre, a földszinti bár eszelősségében is megnyugtató tulajdonosa

szerdánként mereven bámul egy pontot a falon, ahol szerinte egy nap majd kilép

a városban eltűnt nagyapja. Szeretem a beszélgetéseket, amiket ezzel a ponttal

folytat – kizárólag azokon a szerdákon csinálja, amikor front van.

Kitárod a színes, dupla üvegajtót és mosolyogva belépsz,

kezedben azzal a virágosra aranyozott bögrével, amit olyan pofátlanul

lealkudtál a piacon tavaly. Leülsz, beszélsz hozzám, de nem hallak. Nem hallom

a hangod. Az még nem érkezett meg hozzám. Menjünk, reggelizzünk a teraszon,

mondom, amikor épp nem mozdul a szád. És közben azt kívánom, Perejaszlav ne

hívjon még egy ideig, a Tarasz Sevcsenko emlékest helyszíne úgysincs meg,

ráadásul tizenöten leszünk maximum, beleértve a gordonka triót is, szóval ráér még

a télben megfáradt ukrán tavasz.

Mire kiülünk a teraszra, már megérkezem egészen. Érzem a

szád a nyakamon, hallom, ahogy káromkodsz örömödben, mert meghozták a sült

halat, látom, ahogy az elviselhetetlenül boldog retriever, Aziza fellöki a sült

halas fiát a kapu előtt, és elindulok a konyhába, hogy az utca kövén landoló

hal helyett készítsek valami reggelit magunknak. Miközben pirítom a szalonnát,

az ukrán polihisztor, Sevcsenko estjének egyik főcíme libeg be a szemem elé,

könnyedén úszik a levegőben a tragédia, mint egy fuvallatnak álcázott

homokvihar: „I. Miklós ítélete: ’Szigorúan tilos írnia és festenie’ “.

Mindig azt gondoltam, ha az ember párhuzamos életek között

jön-megy (ráadásul ilyen kiszámíthatatlanul), akkor ennek az egésznek van annyi

előnye, hogy amikor az egyikben vagyok, nem gondolkodom a másikon, pláne nincs

bűntudatom, főleg nem hiányérzetem. De van. Kurva nagy baromság ez így. Ki

akarna ezen a casablancai teraszon egy perejaszlavi kultúrház áprilisi

programján gondolkodni?

Az utcáról zene hallatszik fel. Olyan ez a zene, mint

amikor valamit csak kóstolgatni tudsz, csak lassan férsz hozzá, mert túl forró

vagy túl csípős, pedig te szíved szerint teletömnéd vele a szádat és még a

ruhádba is beletörölnéd, hogy hosszú időre beleszáradjon.

Dühös vagy a hal miatt, csitítalak, magyarázol, „gyere,

együnk valami zsírosat”, mondom, nézlek, eszünk, nevetünk, öltözünk, szinte

indulunk.

– Ugye milyen jó itt? Békés és bátor. Ha nem mozdulok,

olyan, mintha a soha megölelné az örökkét. Egyik este kiülhetnénk a teraszra,

te, én meg az idő, és egy vacsorába sűríthetnénk a végtelent – mondom.

– Én jobban örülnék valami grillezett húsnak – mondod.

Nézel rám. Érteni akarsz, de jobban szeretnéd, ha inkább

hallgatnék. Azt gondolod rólam, mindig összezavarom a nyilvánvalót, a békéset.

Csak csendet akarsz, jelenlétet, ölelkezést, játékot. Helyette a szemem

árnyékát látod, ami tulajdonképpen egy szeles ukrán délutánról mesél, abban a

sötét szobában, ami otthonos, de hideg, és ahol lefeküdtem este, mielőtt felébredtem

itt melletted. És ahol magára hagytam azt a szerencsétlen sorsú humanistát, a

gordonka triót és mindenkit, akik sokáig az életemet jelentették.

Két éve kezdődött ez az egész. Perejaszlav hirtelen szürke

lett, fáradt és fullasztó, nem színezte meg sem emlék, sem terv. Aztán egy

közönyös estén lefeküdtem és reggel itt ébredtem melletted. Az én párhuzamos

valóságomban. Fantasztikus volt. Felszabadító. A hatalmas zöld teraszt láttam

meg először, amikor kinyitottam a szemem, meg azt a többszáz éves fát, ami

olyan vigasztalóan borul rá az elmúlásra. (Hozzátartozik az igazsághoz, hogy

volt egy párhetes kitérő egy norvég kis faluval is, de szerintem az csak valami

rendszerhiba lehetett.)

És most két valóságban élek. De nem mindkettőben vagyok

jelen. Érzed, amikor valójában nem vagyok itt, még ha látsz is. Utálod, tudom.

A hiány szülte beteljesülés, és a beteljesülés provokálta hiány. De többnyire

fogalmam sincs, melyik helyen kelek másnap, és miért éppen ott. Mi tart itt, és

mi űz el? Az ébredés helye sosem biztos.

Ahogy szaladunk le a lépcsőn és kikanyarodunk a térről a

széles utcára, ami a sós tengerhez visz, elkezd bennem tekeregni a gondolat,

hogy nemsokára választanom kell. Nem lehetne, hogy Sevcsenkot leültetem

Pierrnél? Együtt néznék azt a pontot a falon. Sevcsenkónak van 200 év előnye és

némi tapasztalata a halottakkal, Pierre-papa talán jobban hallgat rá és előjön,

ha szépen beszél hozzá ez a szerencsétlen sorsú nemzeti hős. Adnék neki papírt,

hadd fessen, hadd írjon szabadon. Jobban járna vele, mint egy emlékesttel.

Mindeközben mi véres húsokat grilleznénk ropogósra a

teraszon, hátha az illat átcsal másokat is ebbe az életbe.